Focus on the history of the IOR

"Lo spirito e l'intento di questa regolamentazione è quello di promuovere le regate di yacht d'altura in condizioni di mare aperto di vari progetti, tipologie e costruzione su una base giusta ed equa" (1969)

“It is the spirit and intent of the rule to promote the racing of seaworthy offshore racing yachts of various designs, types and construction on a fair and equitable basis” (1969)

“It is the spirit and intent of the rule to promote the racing of seaworthy offshore racing yachts of various designs, types and construction on a fair and equitable basis” (1969)

From RORC to IOR: the first period

The history of the International Offshore Rule (IOR) is a fascinating tale of innovation, competition, and transformations that has left an indelible mark on the world of offshore sailing.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the sailing scene was dominated by two distinct metric tonnage rules, established starting in 1907: the RORC, which favored narrow and heavy boats with deep keels, and the CCA, which rewarded wider and more stable hulls.

The fragmentation of regulations and the different design philosophies prompted industry professionals to seek a unified system that could reconcile performance and safety requirements.

After years of discussions and studies, in 1969 the collaboration between the representatives of the RORC-Royal Ocean Racing Club and the CCA-Cruising Club of America began, with the support of the ORC, leading to the birth of a new rule: the IOR, officially adopted in 1970, presenting it to the IYRU-International Yacht Racing Union assembly (the first world organization for sailing sports founded in 1907 to standardize norms and standards of measurement in sailing). This new system, based on complex and combined geometric measurements of the hull, sails and structural elements, introduced the concept of "rating" – a coefficient that allowed boats of different designs to compete on an equal basis – and marked the beginning of a revolution in sailing design.

The IOR was adopted for the first time in Italy in 1970 by the Yacht Club Italiano of Genoa.

The 1970s

The 1970s represented the golden age of the initial development of the IOR. The rule was quickly adopted in some of the most prestigious offshore competitions, such as the Admiral’s Cup, the Whitbread Round the World Race, the Fastnet Race, and the Sydney-Hobart. During this period, designers – including prominent figures like Olin Stephens, Doug Peterson, and Bruce Farr – began to fully exploit the possibilities offered by the new regulation. Thus, boats characterized by a sleek bow and a wide stern were born, capable of maximizing measured length and achieving competitive performance. The system, extremely innovative, also encouraged some extreme design choices, which often led to bold and innovative structural solutions, but not without challenges.

The IOR process involved a Council made up of numerous technical Committees, responsible for making the necessary updates to the rules and formulations for the measurement calculations published in each national sailing confederation year after year. From this structure, the issuance of IOR certificates emerged, which, with the advent of the first computers, quickly reached thousands around the world.

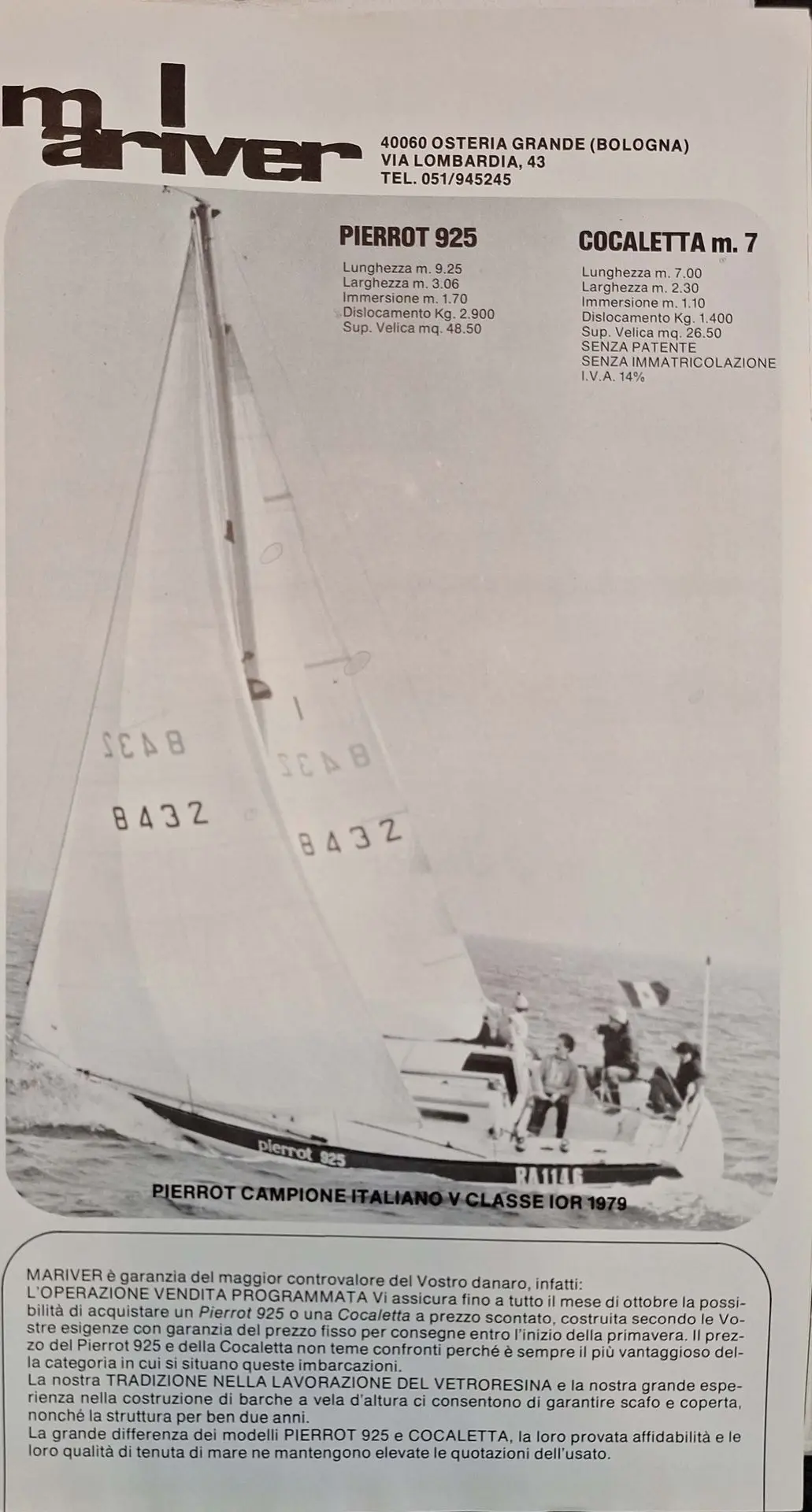

The success of this regulation, combined with the emergence of new design and production technologies, allowed for an unprecedented spread of fiberglass sailing fleets, with an exponential flourishing of shipyards of various sizes everywhere and a strong consolidation of product and market among the more industrial shipyards.

The design trend, developed from the maximum refinement of the application of measurement rules, was to create boats that were increasingly longer and lighter compared to the early IOR, thus guiding the ITC (that is, the aforementioned Committee for Regulation and Certification) to identify new coefficients, which led to significant clashes with manufacturers and designers who had to push for extreme optimizations.

The IOR system identified its own rating classes, each with its own annual world championship: One Ton, Mini Ton, 1/4 Ton ,1/2 Ton, 3/4 Ton and Two Ton.

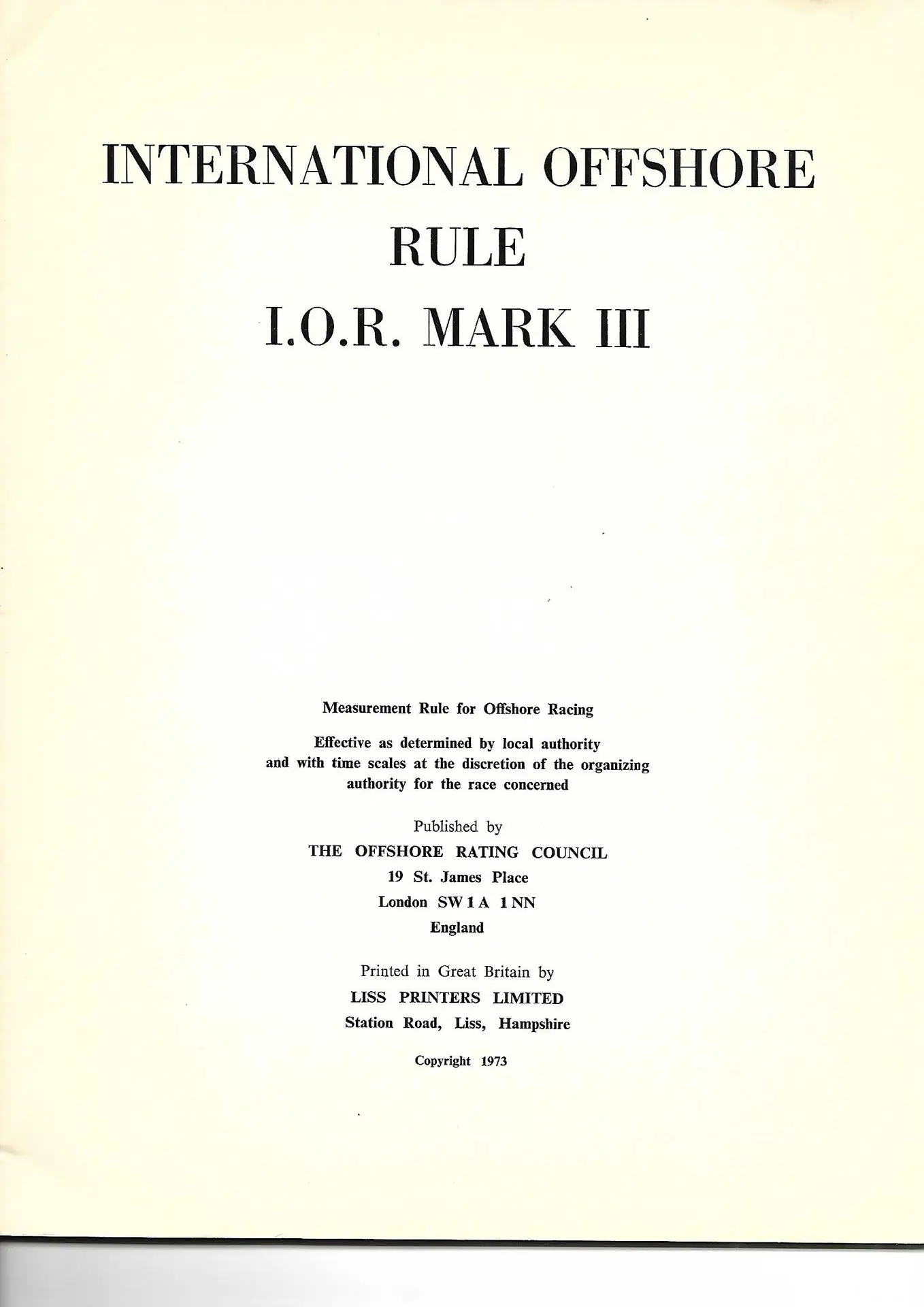

The rating classes were born from a criterion based on the measurements of the hull (length, maximum beam, freeboard, fore triangle), the boom, the mast, and combined with a formula to calculate the inclination (to trace the stability of the boat). These measurements were balanced by possible penalties, and the result of the formula was the IOR rating measured in feet. This rating was directly proportional to the presumed speed of the boat. Therefore, the rating classes originated from this calculation (for example, the rating of a 40-foot boat - corresponding to One Ton - corresponds to an IOR rating of 30.55 feet).

Famous is the description made by the great designer Finot (also renowned for his contributions to many successful productions such as the French shipyard Beneteau and the first Cantieri del Pardo, the Grand Soleil 34) in 'Elements de vitesse des carenes'.

The 80s and early 90s

In the 1980s, the IOR reached its peak in terms of popularity and prestige, along with the definitive emergence of great architects such as the New Zealander Ron Holland and boats produced with great lineage (for example, think of the Finnish 'cygnus' designed by this architect).

Some designers began to exploit certain "loopholes" in the regulations to create increasingly competitive boats, giving rise to designs with exaggerated hull sections and configurations that, while ensuring high speeds, could compromise stability and safety. The tragedy of the 1979 Fastnet Race was already a warning sign, as numerous capsized yachts and a series of casualties highlighted the limits of extremized boats. These events forced the sailing community to review and update the regulations, introducing stricter safety criteria and technical modifications to the formula.

Still, between the late 1980s and the early 1990s, the IOR was a reference for excellence in boats but began to show some uncertainties, which also reflected in the production landscape. The frequent revisions and rapid developments in sailing designs led to a very short competitive lifespan for the vessels, which often remained at the top for only 2-3 years. With the advancement of technology and the now-established introduction of new materials – such as fiberglass, which progressively replaced wood starting in the 1970s – and increasingly sophisticated construction techniques, the need for a new rating system arose.

Thus, in 1994, the IOR was officially replaced by the IMS (International Measurement System), even if some boats presented after 1994 and up until the end of 1995-96, had still been designed on IOR criteria; the IMS system, on the other hand and in reality, had already been used alongside the IOR since 1985…

Subsequently, the IRC and ORC rules replaced the IMS, featuring a design that is quite different in style and technicality.

The new frontier Classic IOR

Today, although the IOR is no longer used in top-level competitions, its impact and legacy are still very much in evidence. Boats designed according to this rule, with their distinctive and often bold shapes, continue to be popular in vintage regattas and restoration initiatives, which aim to preserve a fundamental piece of sailing history. Furthermore, the emergence of a “Classic IOR” class in the world of classic boats and in many race notices, testify to the interest in this system and its historic role in shaping design and competition in the world of yachts to become today the new frontier of classic sails and a true ‘classic’ of sailing.

Today, on the other hand, the CIM provides for the admission to the IOR class only those designed and produced before 1984 and if in possession of an original IOR certificate of the time (moreover, a document not obligatory at the time for navigation if one did not officially race in that class). This CIM rule therefore excludes at the moment excellent IOR designs even from very big sailing brands and production series referring to the last IOR period, that is after 1984, as well as all the owners or their predecessors, who at the time had not already decided to race.

In fact, the history of the IOR follows a path that begins with the unification of measurement rules in the late 1960s, going through a period of great innovation and competition in the 1970s and 1980s, until its decline and replacement in the 1990s. So well beyond 1984, beyond merely possessing an original certificate and not just one-off.

In any case, the IOR remains a milestone in the world of sailing, which has left a lasting legacy in the design of yachts and in the dynamics of offshore racing to the point that today it is considered the priority for the new development of historic sailing and a formidable tool for introducing the youth world to classic sailing and for the indispensable development of artisanal and professional sailing skills necessary for the maintenance and survival of this gigantic world fleet.

Classic IOR and the action of the 'Royal Heritage' Fleet

For all the reasons outlined above, our association aims to enhance the classic sails of this period by placing them alongside the nobility of vintage sails, as a new tool for historical and cultural dissemination of maritime values and training for the professions of classic boating, combined with the values of sustainability towards young people and families. The future of vintage sails and their impact on culture and employment will also depend on the awareness and knowledge of what was qualitatively produced around the IOR period and how much of this period can be valued by organizations in social terms and lifestyle. The simultaneously exaggerated and romantic lines of the IOR, its series productions made with revolutionary technology and materials for the time, were emerging while identical emotions were living in parallel in industry, art, architecture, music, cinematography, politics, and society, now part of history. It is necessary to understand, know, and comprehend them to make the context of the IOR period a 'classic' in its cultural complexity, with completeness.

Even more so, sailing needs professional and artisan skills that can deal with an increasingly important classic sailing fleet with ability and passion: the associative challenge is therefore to combine moments of sociality, culture and fun with the stimulus of creating supply chains of expertise as the future and hope of sailing. In other words, the goal is to create a fleet of Good.

(Images taken from examples of promotion of classic sails from the era)